The path to wholeness is riddled with ruptures, held open by frayed and fragmented threads. I’ve come to see these ruptures as birth canals—portals through which Goddess reconciles the irreconcilable.

We all carry threads that have made the great traverse. Here, I share some of mine.

I come from a lineage of liberation leaders whose legacy was forged in alliances that were rarely recorded in history books. My great(x3) grandmother, Abadi Bano Begum (Bi Amma), organized the largest Hindu-Muslim coalition to rise up against the British Raj.

Her sons, my great-great-grandfathers Shaukat Ali and Mohammed Ali Jauhar, organized the Khilafat Movement: a supranational coalition weaving India’s liberation with indigenous resistances across the Arab world to stand up for sovereignty in opposition to the Zionist project and colonialism.

Mohammed Ali Jauhar was buried at Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem in 1931, at the request of the Grand Mufti of Palestine. His final resting place stands testament to the solidarity between India’s liberation front and the Palestinian struggle.

I was born in Redondo Beach, California. My mom was only fourteen—a child bride. My dad, twenty years older, had left the cocaine trade and become a con man.

When I was three, he moved our family to Pakistan after a million-dollar scam left him with a price on his head.

At age seven, two men with Kalashnikovs stormed his office, killed everyone inside. My dad survived, but we fled that night, returning to the United States.

It was the start of a childhood spent in constant motion—between countries, between worlds.

At thirteen, my family moved back to Pakistan. Between 2000 and 2004, I witnessed severe refugee crises, the weapons trade, extreme poverty, human trafficking, and the regional impact of the U.S. invasions on Iraq—all while living under martial law, amid car bombs and checkpoints.

My dad exposed us to the world’s gritty underbelly. We travelled by road through treacherous terrain across Pakistan into the edges of the Indo-China borderlands.

Instead of going to high school, I was schooled by the vast contrast of the human condition. My upbringing opened me to the depths of humanity’s ruptures and the transformative potential that lies therein.

During this time, the global textile industry’s use of azo-dyes was also poisoning the soils of the Indus Valley, leaving them infertile.

As we travelled, I saw thousands of villagers—subsistence farmers—displaced from lands that had been cultivated since the dawn of agriculture.

In this crucible of dislocation, I felt a fire growing within me to answer the question: How do we create a world without displacement and hunger?

At seventeen, I returned to the U.S., obtained my GED as a homeless youth, studied soil science as an undergraduate, and later entered a PhD program at UC-Irvine.

Two years in, I knew I didn’t want to spend my life refining climate models that would only feed the next IPCC report.

I left my PhD program and moved to Iowa—a state with four times as many pigs as people.

At Iowa State University, I pursued a dual Master’s in Sustainable Agriculture and Community & Regional Planning—learning everything I could about the death cult masquerading itself as America’s breadbasket.

I spent the next 15 years working on food justice—securing land for refugee farmers, directing a program of 65+ community gardens, and advancing initiatives with the Chicago Food Policy Action Council.

Hoping to drive change on a larger scale, I turned to federal policy—organizing grassroots farmer coalitions to shape U.S. food and farm policies, only to watch hard-won gains collapse again and again with a change in administration.

The lesson was clear: systems built on fragmentation reproduce fragmentation.

Meanwhile, my yearning to orient to wholeness grew.

This yearning led me to complete a Master’s in Transformational Leadership and Coaching at Wright Graduate University—a rigorous program that blended hands-on coaching with research-based methods in neuroscience, psychology, and related fields to address mindset, trauma, and intimacy.

It was a rich and embodied exploration of human emergence that gave me the skills to grow myself while supporting others in their unfolding.

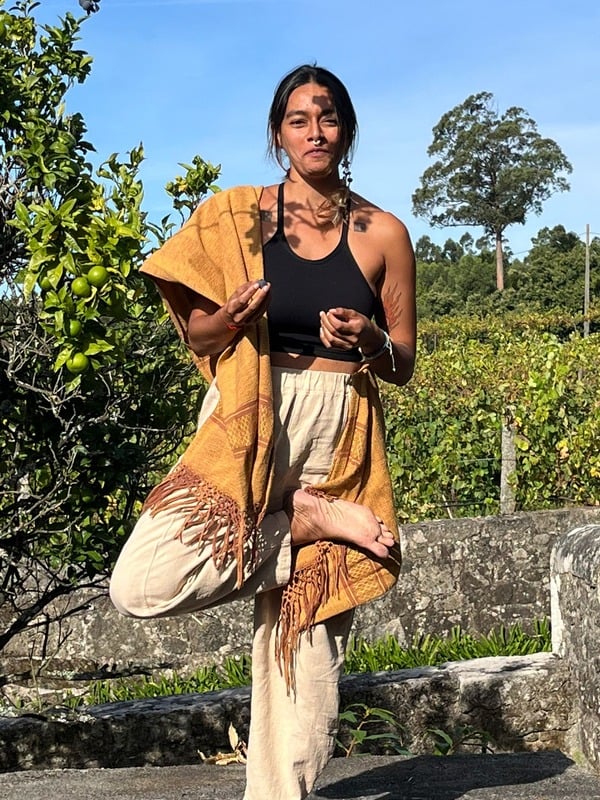

I was also healing my body—aligning my fascia with structural integration and other forms of bodywork.

My alliances with plant medicines—Mother Ayahuasca, Father San Pedro, Grandfather Peyote, and others—opened me further to healing at the deepest levels, transforming my life radically.

After years on the healing path, I still struggled to find my way. The skies were wide open, yet I felt like a pilot without a compass—unsure where to fly.

When Marc introduced me to Circle’s teachings, I began to work with greater clarity—anchoring in my own essence to come into coherence.

With my Zapotec family, I hold a tapete we wove with symbols from the Palestinian keffiyeh and offered as a prayer in solidarity with oppressed peoples everywhere.

Circle brings it all together for me, revealing life as a sacred dance between form and formlessness, always in relationship with the whole.

By releasing what doesn’t align with my essence, I’ve opened myself to soul alliances who remind me: everything we touch, also touches us.

I am especially grateful to my adoptive family of Zapotec weavers in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca. Their wisdom has taught me how the ten-thousand-year-old tradition of weaving embodies a cosmology of wholeness—a teaching that continues to guide my path with Circle.